Within a mile of last Friday's tragedy at the Astroworld Festival is the largest and most advanced Hospital District in the world. Yet medics were reportedly understaffed and poorly trained or prepared for the 8 deaths and hundreds of injuries reported so far. Sometimes two seemingly opposite facts co-exist in such a close proximity to each other that they highlight the absurdity of the world beyond them. Houston is the city of death and contradictions.

There is always some tragic and disastrous shit going down here. We are far from the only city where people die, but it’s the manner in which they do, and the swiftness by which we move from one event to another, that never ceases to amaze me. You hear “#Houston Strong” before anyone has had a chance to bury their dead. Everyone joins in its chorus to praise our resiliency, while the people who paved floodplains and profited from petrochemical death all sleep very well.

This is the cost of the “Boomtown”, the city that “resisted the recession”. The explosive growth is something you feel here, something everyone is acutely aware of. Not just from the population influx, but the overwhelming sense that Houston is a grind. It’s the newest “world city”, putting itself on the global map for the first time over and over again. Everyone and everything is always trying to find their come-up, and you’d better be careful not to get left in the dust.

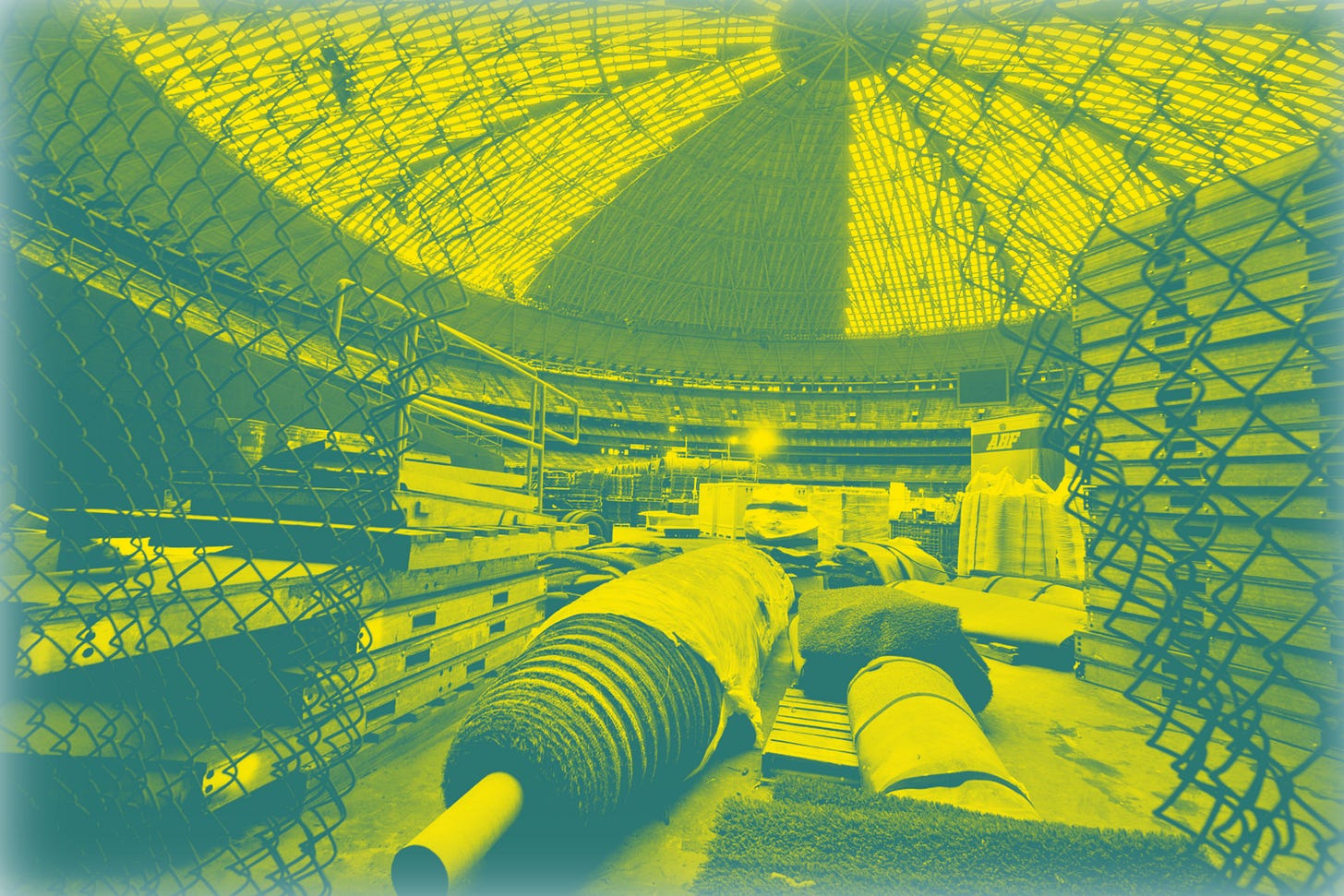

Sometimes we embrace this, I have long said that Houston is a place to live but not visit, you always appreciate what we have because it’s always been more than what we had in the past. It’s so exciting that we’ve become numb to the meat-grinders we’re thrown into. Our instinct for death is the sine-non-qua of the sublime abundance we’ve enjoyed. The whole world gazed at the Astrodome for decades, today it sits empty and will likely never be used again by anyone but rats. It is a sarcophagus for our cherished memories, and a reminder that all good things must end eventually. Life here is live fast, die slow. What comes up must come down, and we’re in for hell to pay for our sins.

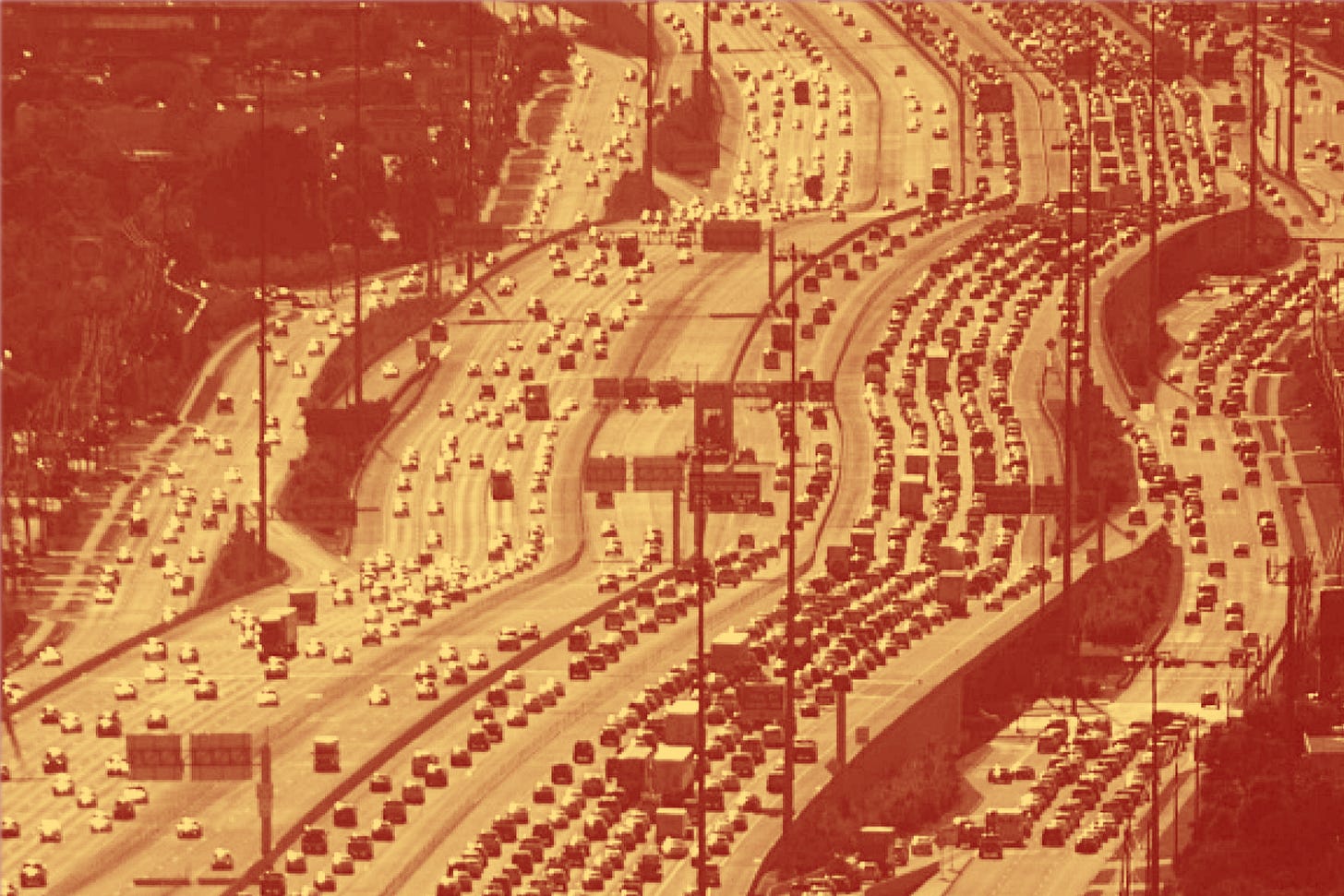

In a lot of ways, Houston epitomizes America’s last gasp as it plunges deeper into a dystopic decline. This city is as plastic as a vase of fake flowers, from a distance they look real and elegant, but the closer you get, the more artificial everything is. It is a symbol of America doubling down on what we think a city should be. Look no further for evidence than the ultra-wide 26 lane I-10, regularly seen covered in bumper-to-bumper traffic. The city’s sea of concrete sprawls for more than 25 miles in every direction. Hundreds of miles of rail would never be enough to offset the oil-addicted death-drive we’ve built this city on. Over 100 people died on the freeways trying to evacuate the city during Hurricane Rita in 2005, a storm that never even came to Houston.

State sanctioned death is injected directly into the air from the plumes of the petrochemical plant smoke stacks. Cancer alleys line the Houston Ship Channel and Galveston Bay. This might be one of the few coastal cities that builds away from the coastline as if it doesn’t exist. Miles away from where you get cancer for being born black or brown in Houston, the rich and more travel from all over the world to get first class cancer treatment at M.D. Anderson. Your zip code determines your life expectancy in a difference of 20 years.

Hellscape is the only word to describe the terrain of this city. I hope by now, you have seen Parasite (2019) and Squid Game (2021). These pieces of Korean media are symbols of a cultural phenomenon known as “Hell Joseon”, an expression of discontent and misery in the modern Republic of Korea. Both conjure stories which tug at our class hatred and invoke the kind of sentiment we see in our own cultural blockbusters like Joker (2019), which is a major factor in how they’ve been able to penetrate our consciousness. I found the backdrop of a modern capitalist hellscape, one that we can all relate to even if it is also particular, contingent, “foreign”. A hellscape isn’t simply geographic, hellscapes are a relation shared between people, not just within classes, but imposed on one by another.

I want to point to a particular plot device featured in both the aforementioned Korean stories: Morse code. As far as I know, it’s by coincidence that it made its way into both scripts. However, it is vital to the survival of characters and their plot. In Parasite, the differences between Korean and English Morse code are enough to foil an escape. The Korean Morse code that poorer, older, working class people are familiar with is unknown to the rich kid who learns Morse code in scout camping and was raised learning English. In Squid Game, the use of Morse code is not as rich with subtle implications, but serves the same function. It’s a tool of survival and escape within the hellscape.

The hellscape we live in here has its own Morse code. Our own stories of survival are written in it, describing how we tread through the flood waters, breath the cancerous air, navigate 26 lane freeways, and care for our own bodies under a regime of criminalized abortion. Everyone exists within the hellscape, but the codes are different. During the deadly freeze of Winter Storm Uri earlier this year, the homes of the rich and powerful in high rises stayed powered while they looked down upon the freezing masses. When pipes froze and burst and left thousands of tenants without water, landlords told them to use green sludge from a disrepaired pool. They have their code and we have ours, and this holds the hellscape together.

Our city is run and administered by absolute ghouls who are more than complicit with Houston’s death drive. They worship it. The poor are an offering to the altar of death through the acceleration of climate crisis, and wars against unpaved floodplains and the firefighter’s union. The Mayor cannot even avoid a corruption scandal as it pertains to an affordable housing complex. Their code is pumping more and more money towards a billion dollar police budget and counter-insurgency so that we can hopefully never stop them, and making sure all their friends get paid in the meantime.

I want to say “to hell with Houston”, but hell is already here. If you’ve been to a punk or metal show of any kind in the past 15 years here, you’ve probably seen the image below, the artwork to local grindcore band Insect Warfare’s “World Extermination”, by Daniel “Sawblade” Shaw. It’s a dystopic, apocalyptic image of our skyline, and it’s embraced because like the “Hell Joseon” media, it describes our current hellscape, something we’re increasingly arriving at. A few centuries ago, “Houston” meant nothing in minds of the people living here, that had to have been the last time this was a decent place. Nothing good can come from this, every inch is stolen and bathed in blood, cursing us to a damned eternity as payment for our sins. I want desperately to remember when I loved my city, but it doesn’t love us back. I used to have dreams for “Houston” but they died a long time ago. The gateway to another world through the space exploration we used to do has been privatized and sold to Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos as a luxury for ultra-rich misanthropic cynics.

If you do try to escape the hellscape, my suggestion is to not go by bicycle, as this is clearly the deadliest way to travel. Road raging pick-up drivers circle the area that surrounds the city center, eager to run you over with impunity. There can be no escape. I’ve tasted the fruits of other lands and resided in another hellscape, but I always return to Houston, because at least this is the one I know. We’re always just trading one for another.

But I’m done lying to people. I’ll never tell anyone “Houston is great to live in, it’s just terrible to visit!” ever again. It’s a lie we tell ourselves, to cope with the death all around us. The truth is that Houston is the city of death, and after all of the humans have died and only insects remain, the reaper will ride the toxic waters of the bayous that form the veins of the wasteland we earned, collecting the lost and wandering souls who saw the end here.